Book review

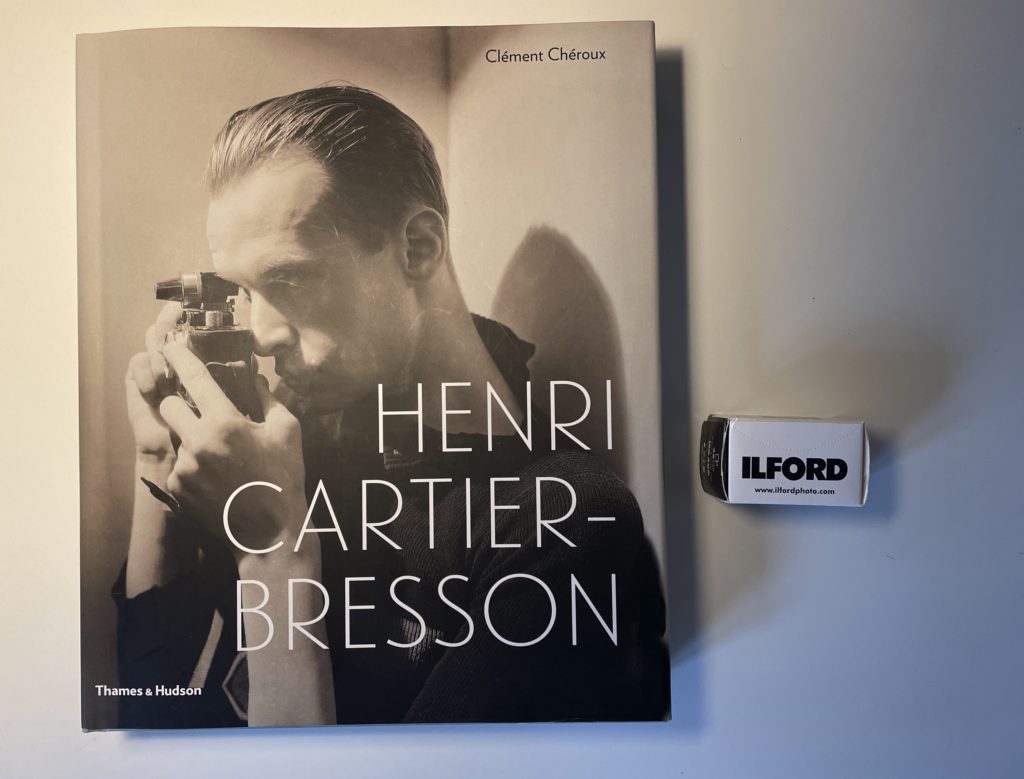

If there is one photographer that every photojournalist or street photographer knows, it is Henri Cartier-Bresson (HCB)! This books takes you through all of HCB’s life: what event shaped him, who he met and was influenced by, his travels to Africa, Cuba, China, India, Spain etc, his work as a reporter for the Communist Press, how surrealism attracted him and influenced his work – the list goes on. Reading this book, you come to understand both how interesting a life HCB lead, but also the historical events that his images document and reflect.

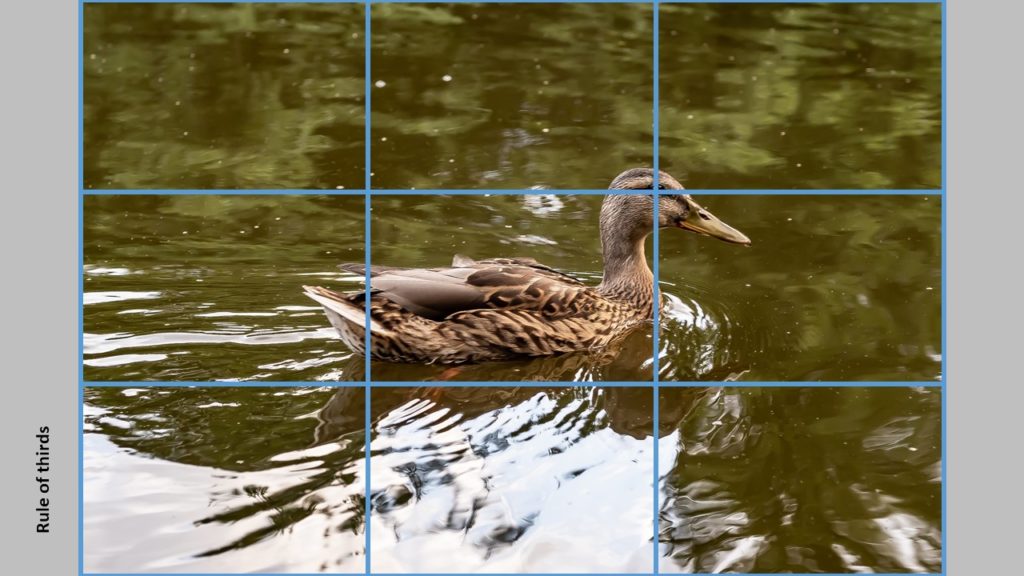

I can’t figure out exactly why I find HCB’s images so stunning. There is obviously his mastering of composition long before all the rules were invented. And his talent for being at the right spot at the right time and on top of that hitting the shutter exactly at the decisive moment. But there is more to it than that. A touch of surrealism that adds a strange glow to his images that continues to fascinate me. No matter how much I analyze the images, the effect on me somehow escapes me just when I think I have it all figured out! And I guess this is exactly where a good photographer and a master of photography separate: the ability to make you look not only a second time, but again and again.

This book is a wonderful collection of 500+ of his images, and as a photographer looking over the should of a master, this is the part that I like the best. Others may find the story of his lift more interesting – for example how he 3 times escaped as a prisoner of war and later became a communist. And later decided to work for many years solely doing photojournalism. This part of the book I also enjoyed, but the pictures! I can wholeheartedly recommend this book if you find his work fascinating like I do.

PS: HCB is quoted for saying that: “In any case, people think far too much about techniques and not enough about seeing”. This remark is more relevant than ever, where YouTubers constantly battle to what extend photography gear matters and if the rule of thirds is to be applied always or sometimes.

Related reading

Understanding a photograph by John Berger

Review: Photo work: Forty photographers on process and practice, edited by Sasha Wolf