Read the light

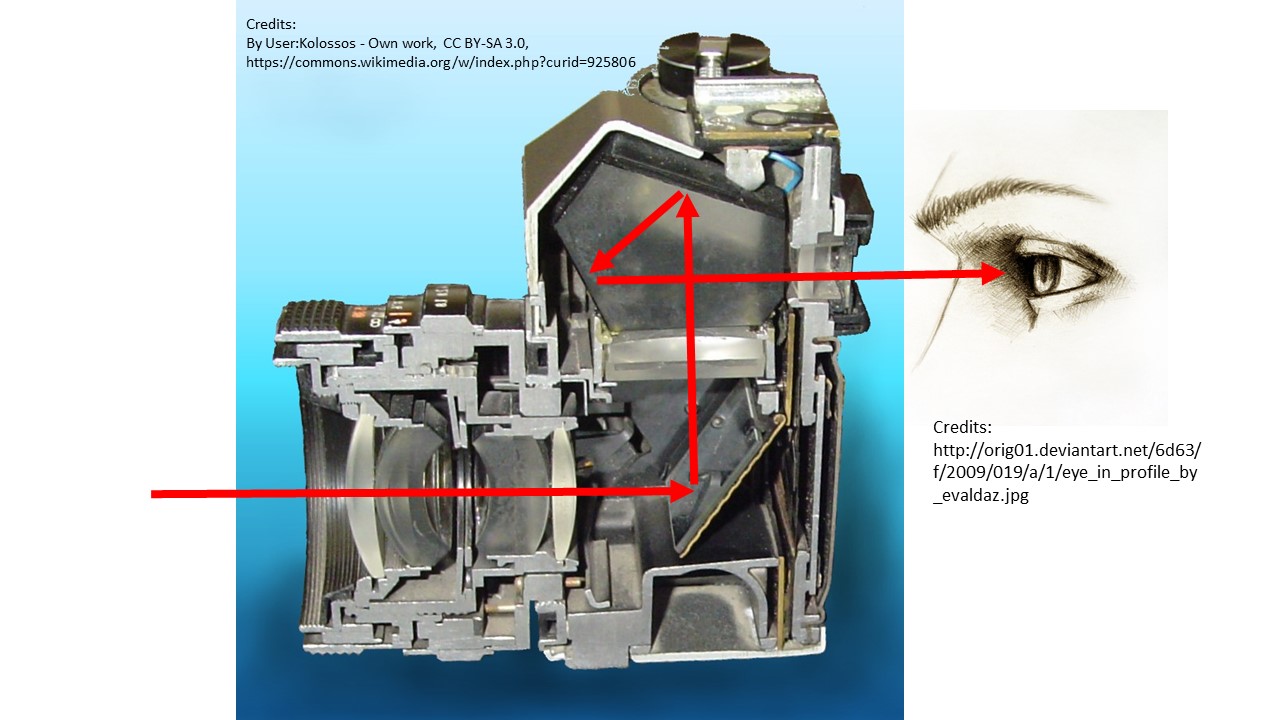

The image sensor has replaced the 35mm film as the receptor of light. This gives many advantages, for example that you don’t have to change film every 24 or 36 images, that you can preview the result immediately and don’t have to wait for the lab to deliver results. Further, you can carry a very large number of pictures on a small memory card and it is easy to transfer the files to a PC for post processing. Most shoot with digital cameras these days, but – just like the revival of the vinyl records – there as some that mix film shooting into their work simply because they like the expression you get this way.

The image sensor is the unit that has replaced where the film used to be – and this is very literally. The sensor sits in the same position as the film used to do and the size is – provided you shoot full frame – also the same (35 mm).

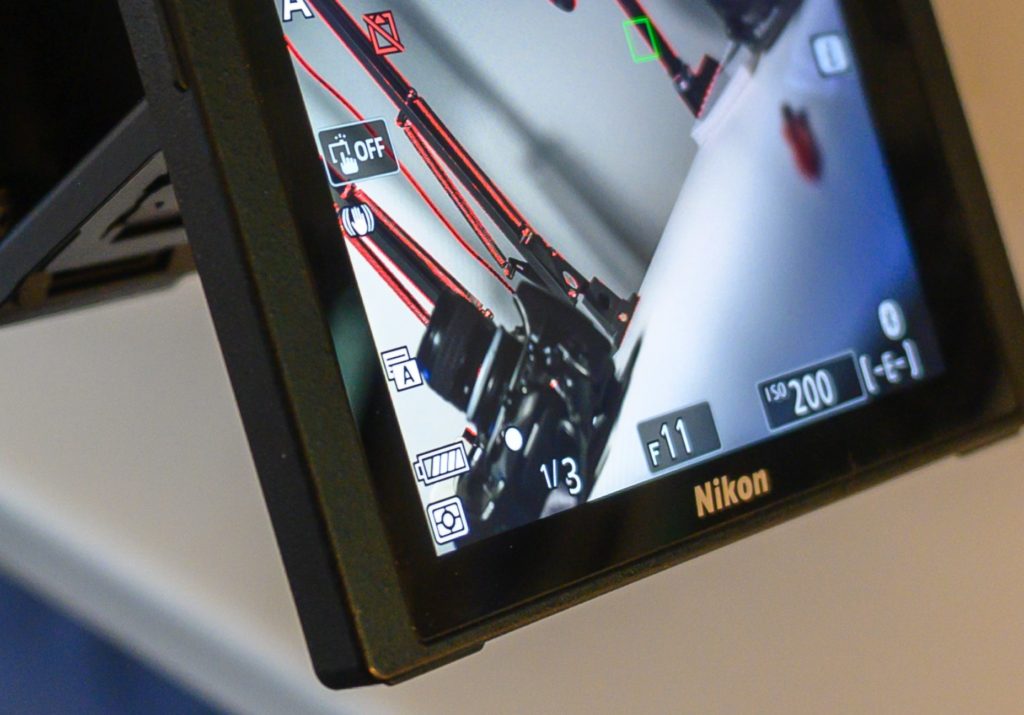

The camera image sensor, here from the Nikon Z50. In a mirrorless camera the sensor is completely exposed when the lens is removed; on a DSLR the sensor is hidden behind a diagonal positioned glass.

The camera image sensor, here from the Nikon Z50. In a mirrorless camera the sensor is completely exposed when the lens is removed; on a DSLR the sensor is hidden behind a diagonal positioned glass.

With the introduction of mirrorless cameras you can now actually see the sensor when the glass is removed from the camera body. This also makes the sensor vulnerable to dust and dirt if you change lenses in the field. With a DSLR, the sensor is to some extend protected behind the mirror.

The sensor is not exposed entirely, as there is a thin layer of glass in front of the sensor; otherwise the sensor would be too vulnerable. You can buy sets to clean the sensor and to blow air onto the sensor in order to remove dust and particles. Never remove dust from the sensor using your breath – it contains moist and that is dangerous for your camera in general and the electronics in particular. Always use a (rocket) air blower for such work.

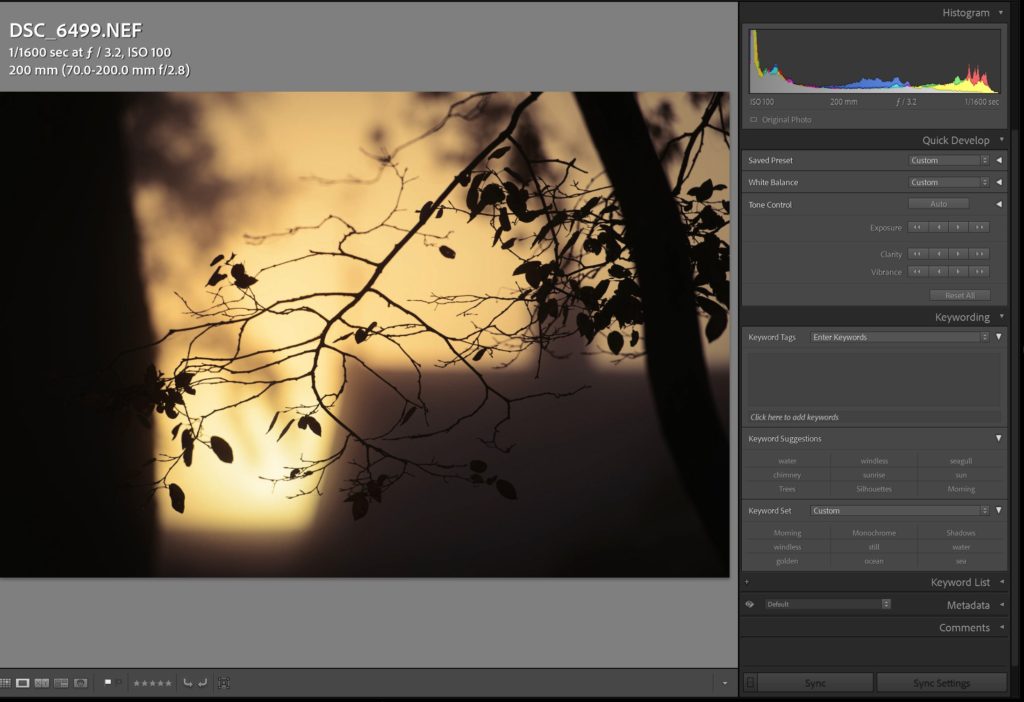

The sensor reads the light just like the film used to do and the values read are then made into an image stored on the memory card in the camera. You cannot change the sensitivity of the sensor, it remains the same as when the sensor left the factory. But you can change the ISO value, which is a factor applied to the light read by the sensor by the cameras image processing software (firmware). Unfortunately, cranking up the ISO means that both signal and noise is amplified, and with a weak signal, it can be difficult for the camera to distinguish between signal and noise. For that reason images taken with high ISO values are grainy and have washed out colors.