I got my Nikon AF-S 85mm 1.8G lens over at mpb Europe for 334 EUR used – this was October 2021. The lens was rated by mpb to be in excellent condition, which in my experience is close to brand new! The same lens from new in Denmark is around 500 EUR, but mind you that here in little Denmark prices are per usual some of the highest in Europe. But still, I find that I save a lot buying used gear in good to mint condition.

The first that I noticed when mounting the lens is how big it is in terms of circumference. It protrudes beyond the f-mount size significantly as the images above and below show. I knew the 1.4G lens is a “dramatic” lens in terms of size, but it surprised me that the same can be said about the 1.8G lens.

The lens does not have a golden ring on the nose, so apparently Nikon does not think this is a professional grade lens; my guess is they left this to the 1.4G lens instead. The body is made up of plastic, and the f-mount is metal as we know it. The feel and appearance of the lens is quite good considering we have left the days of “all metal, all glass and made in Japan”. This one is made in China.

The weight is around 350 grams which is super light, especially considering the lens volume. Although Nikon does not market this lens as weather sealed, I did notice that there is a rubber gasket on the f-mount, so at least dust will have a hard time finding way in between lens and body.

Speaking of the 1.4G lens, your question is probably why I did not buy the 1.4G? I would have loved that lens, but the price tag is around 3 times as much as the 1,8G! And although I love fast lenses, I simply could not cough up the cash to go for the 1.4G.

The lens comes with a lens hood of good quality albeit plastic, it takes Ø67mm filters and there is no issue with moving parts out front, your filter will be sitting in the same position as when you mounted it!

The lens has no aperture ring – all adjustments to aperture are done via the camera body. There is only one button on the lens itself, and that is the auto focus to manual focus switch. The former can always be overruled by manual focus as soon as you start turning the focus ring.

I am happy to say that the focus ring works really well. There is no play as I reported for the 50mm 1.8G lens. The feel of the manual focus ring is not super smooth, but it works ok. The AF-S is as you would expect both silent and fast, but not the fastest Nikkor I have tested. But as this is mainly a portrait lens, maybe some street as well, I doubt that you would need blazing fast AF as you do for wildlife and sports. The built in AF motor allows you to use the lens also with AF on Nikon entry level bodies like the D3x00 and D5x00.

The distance scale is there working from the minimal focus distance of 0.8 meters to infinity, although my own non-scientific testing showed that I could get 5 cm closer than that. They have even found space for DoF markings on the distance scale, although only for f/16. There are 7 rounded aperture blades, which is a bit on the low side, especially for a portrait lens where the bokeh per tradition is vital.

The lens comes with what Nikon calls SIC – super integrated coating, and the dampening of flare when pointing the lens to a street light at night is some of the best I have ever seen. The SIC is really sick, pun intended! There is no ED glass at all, so it is really a “back to basics” construction with no modern fancy stuff, but just good glass in a relatively simple construction.

Performance

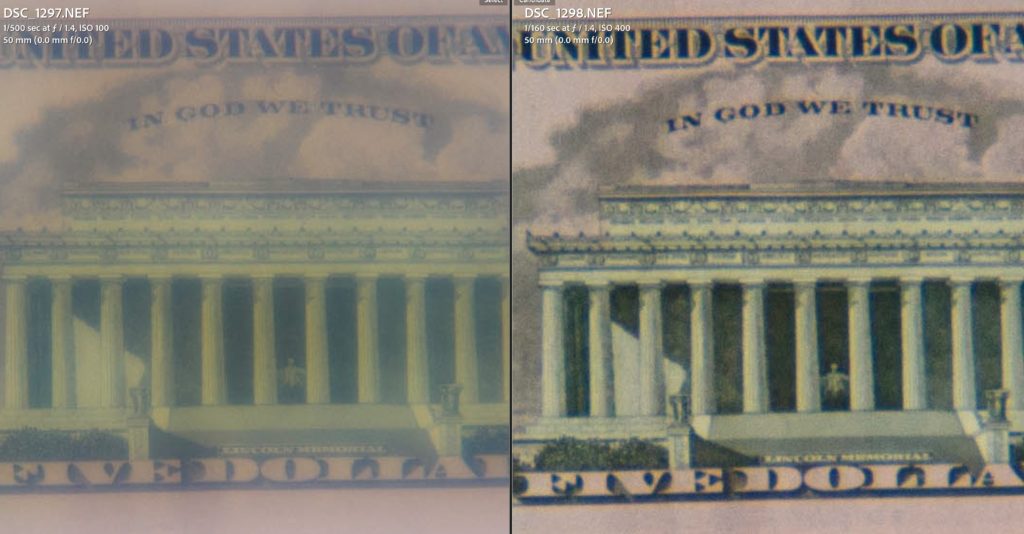

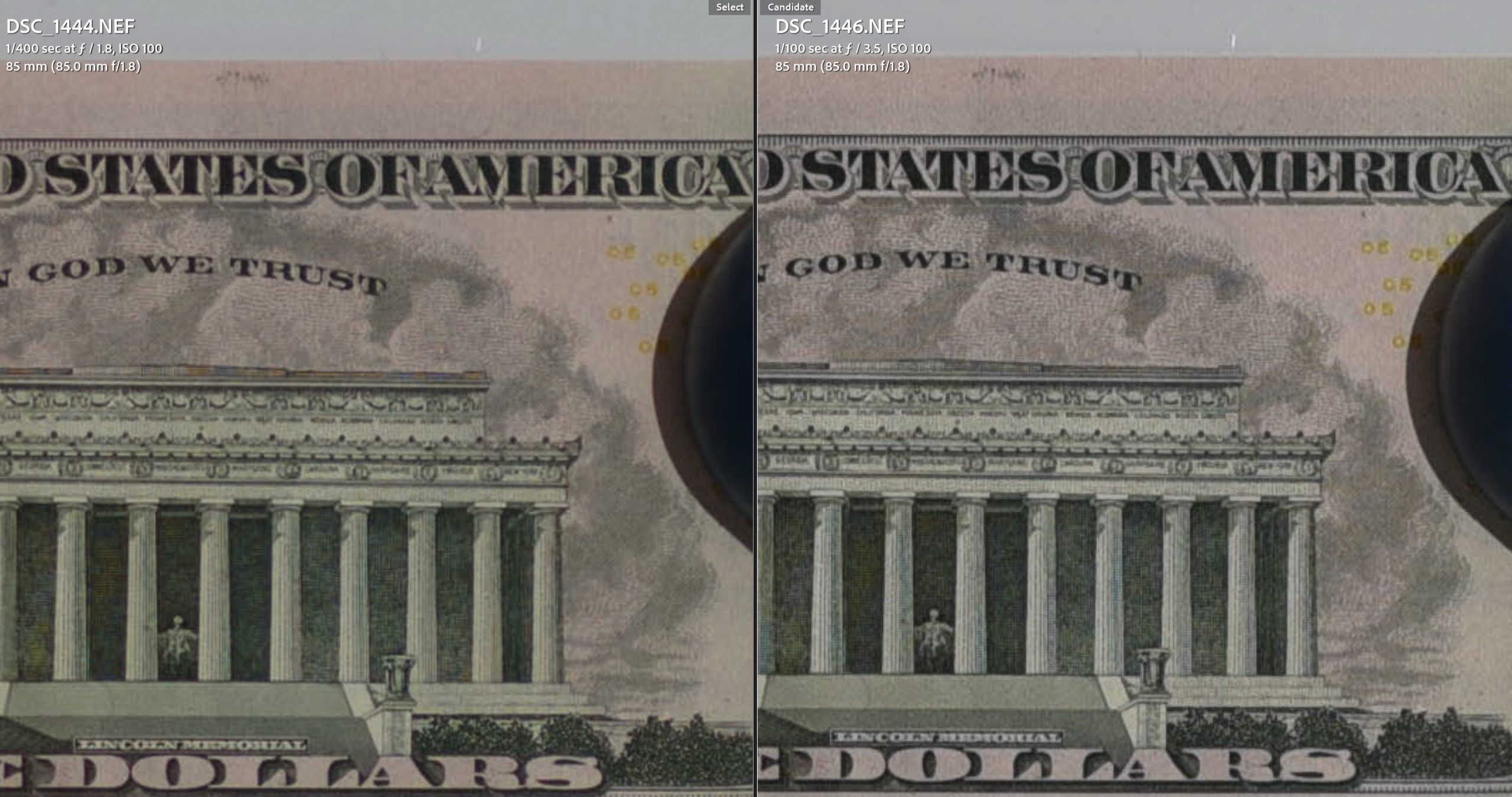

This lens is sharp! You may have guessed that if you took a look at the MTF chart from Nikon or read other reviews, but it really is! Take a look at these two images from Lightroom measuring the center sharpness at 300%:

Wide open left (f/1.8) and stopped down a bit to the right (f/3.5). If you have seen other of my reviews, you know that I like to shoot a whiteboard with a few dollar and EUR bills to test sharpness and contrast, and when I can read the state names, then I know I am dealing with a very sharp lens. In this case I can read that NY is to the rightmost! The sharpness gets slightly better stopped down, but this is impressive performance!

Looking at the corner sharpness, it gets even better (still 300%):

This is from the bottom left, and the performance wide open (left) is impressive! I may be able to see that it stopped down has slightly better contrast (look at the white in the EUR sign top left), but still this is some of the best corner performance wide open that I have ever seen! Well done Nikon!

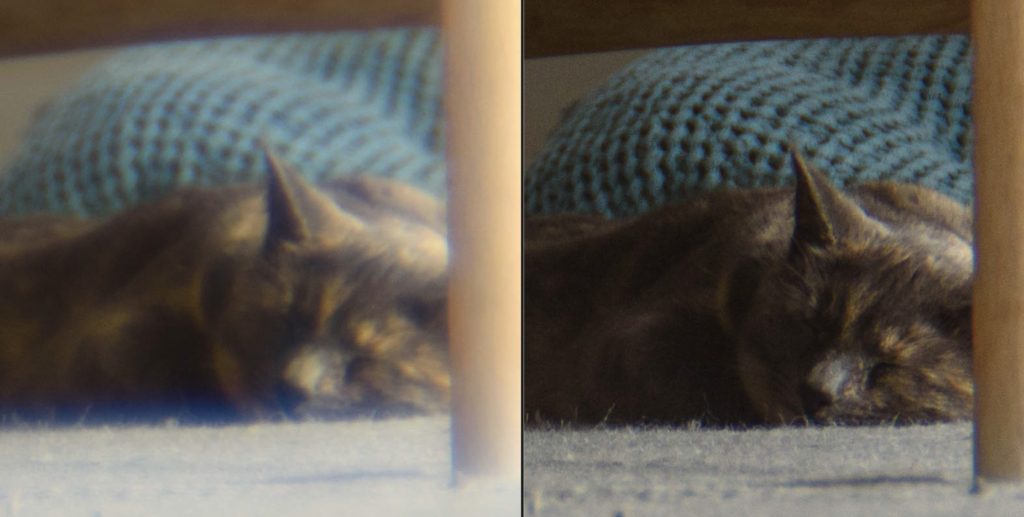

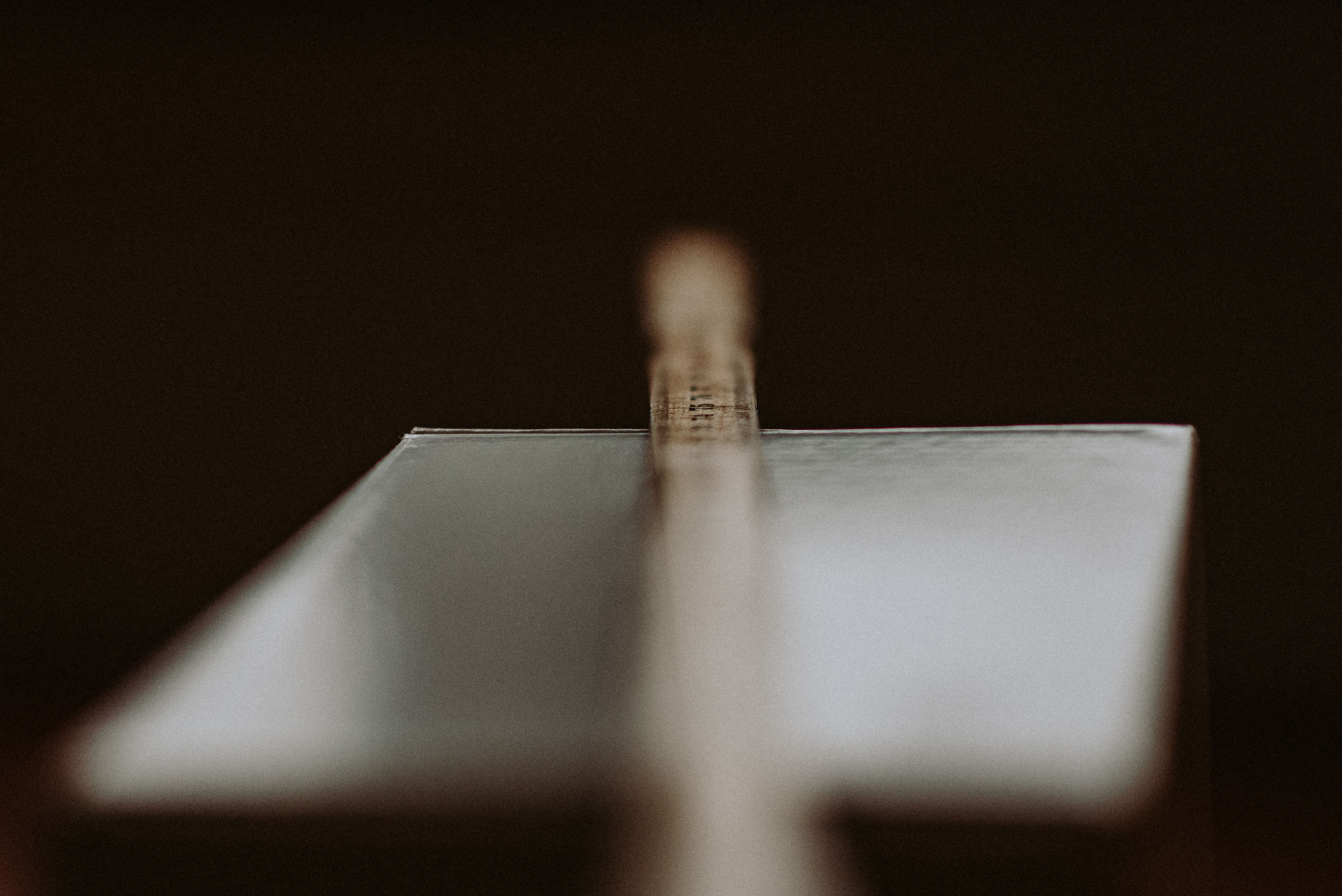

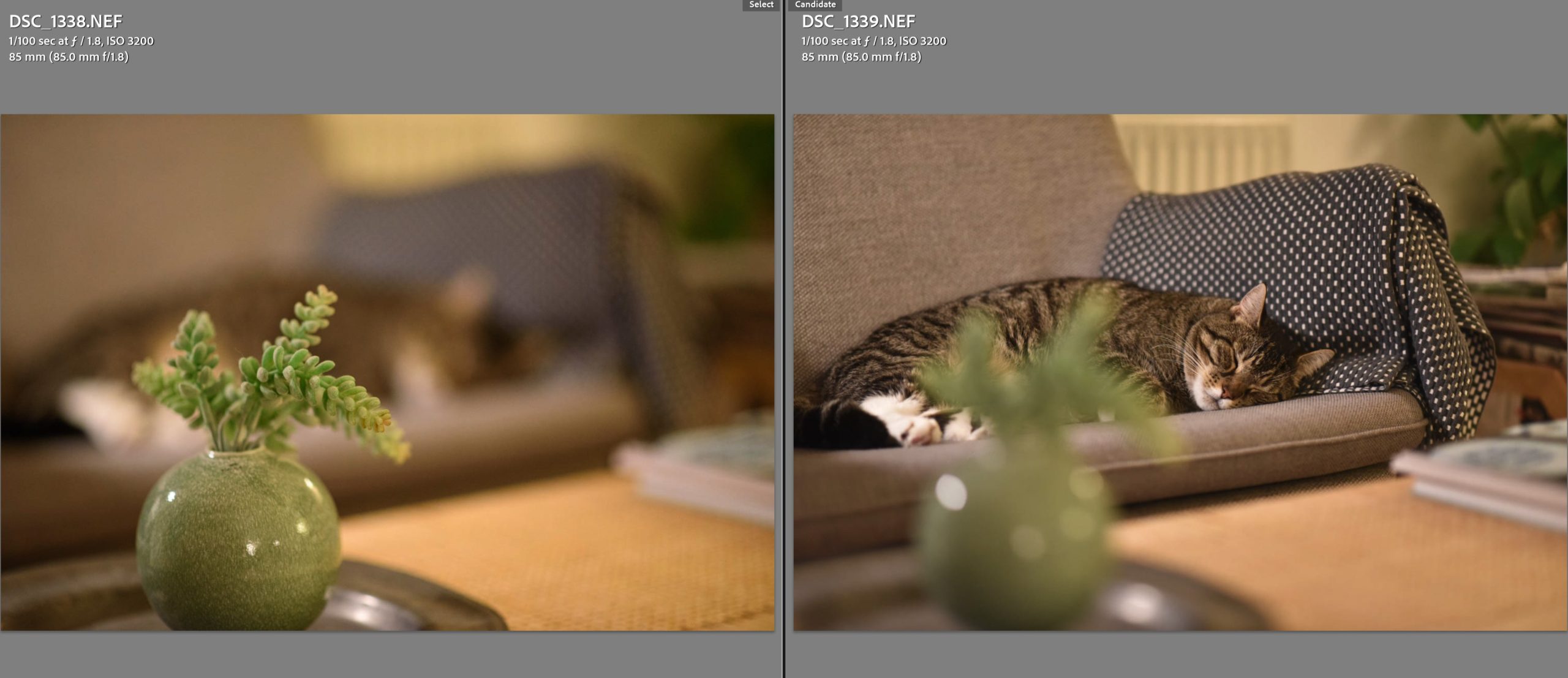

And when you shoot at f/1.8 you really get a shallow depth of field! I know that f/1.4 or even f/1.2 will give you more, but still:

Same motive, but 2 different focus points: left the flower in the foreground and right the cat in the couch. Even when there is only 1.5 meter between the subject and your background elements, the latter gets rendered beautifully out of focus!

The bokeh I have found to be beautiful. When shooting wide open, the aperture blades are not engaged, and hence you of course get nice round bokeh balls, although the bokeh towards the corners tend to be more oval and shaped like an American football:

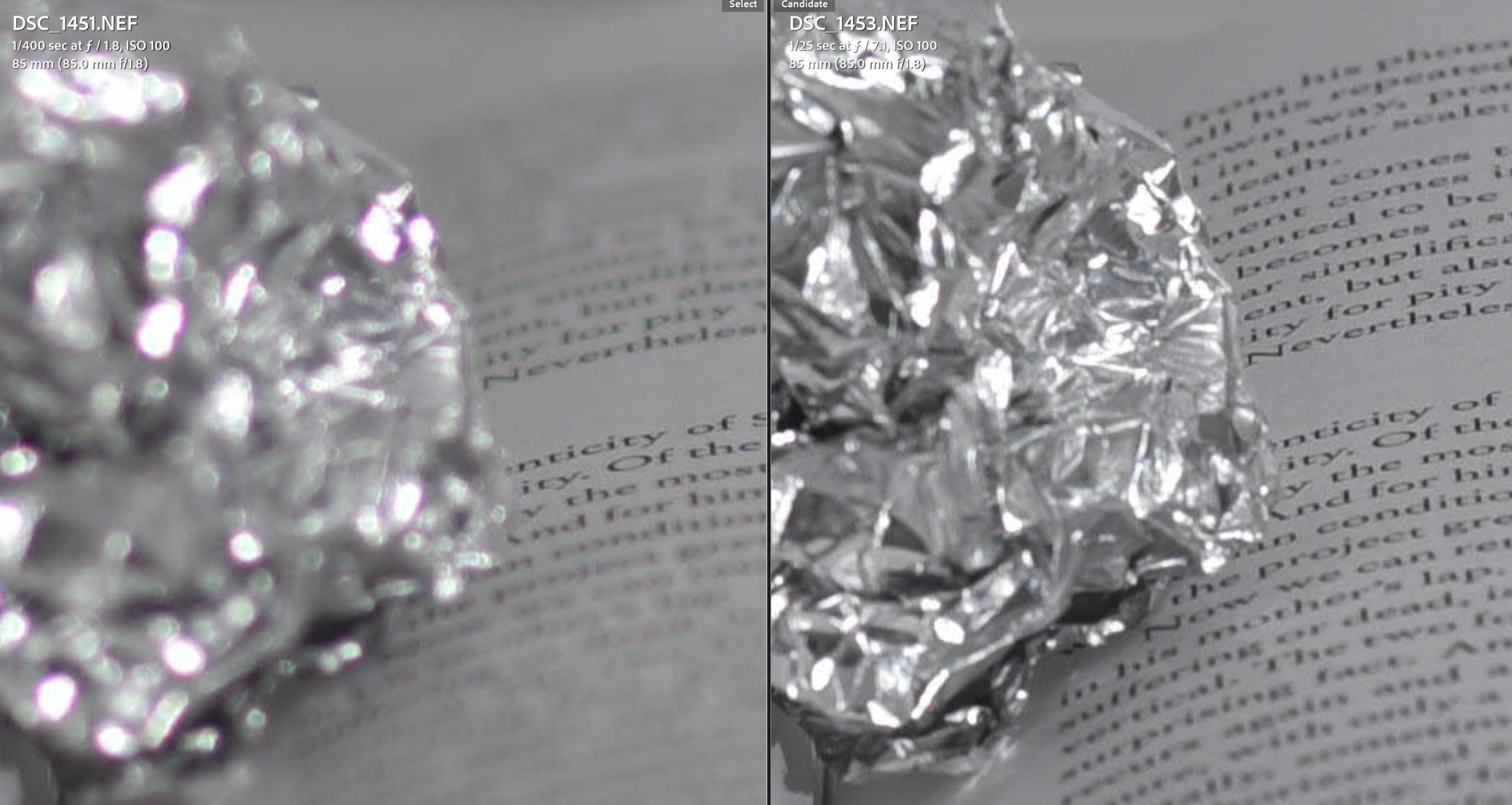

I had high hopes for aberrations, but apparently I can get any lens to generate at least purple fringing:

Wide open to the left you can see purple fringing in the high contrast zones of the tinfoil. Not so much stopped down to the right (f/7.1). So there is a bit of aberrations and shooting streetlights at night (yes, a hobby yours truly practices) it gets noticeable – but I have always been able to remove it in Lightroom by pulling a few sliders. And speaking of streetlights at night, my test of flare showed that this lens has some of the best control of flare that I have ever seen.

The lens does suffer from focus breathing, so if you are considering it as an option for videography you may find that this is a showstopper. Especially when you ALSO consider how well flare and ghosting is controlled by this lens (videographers for some reason love this stuff and do not want to well dampened lenses in this regard).

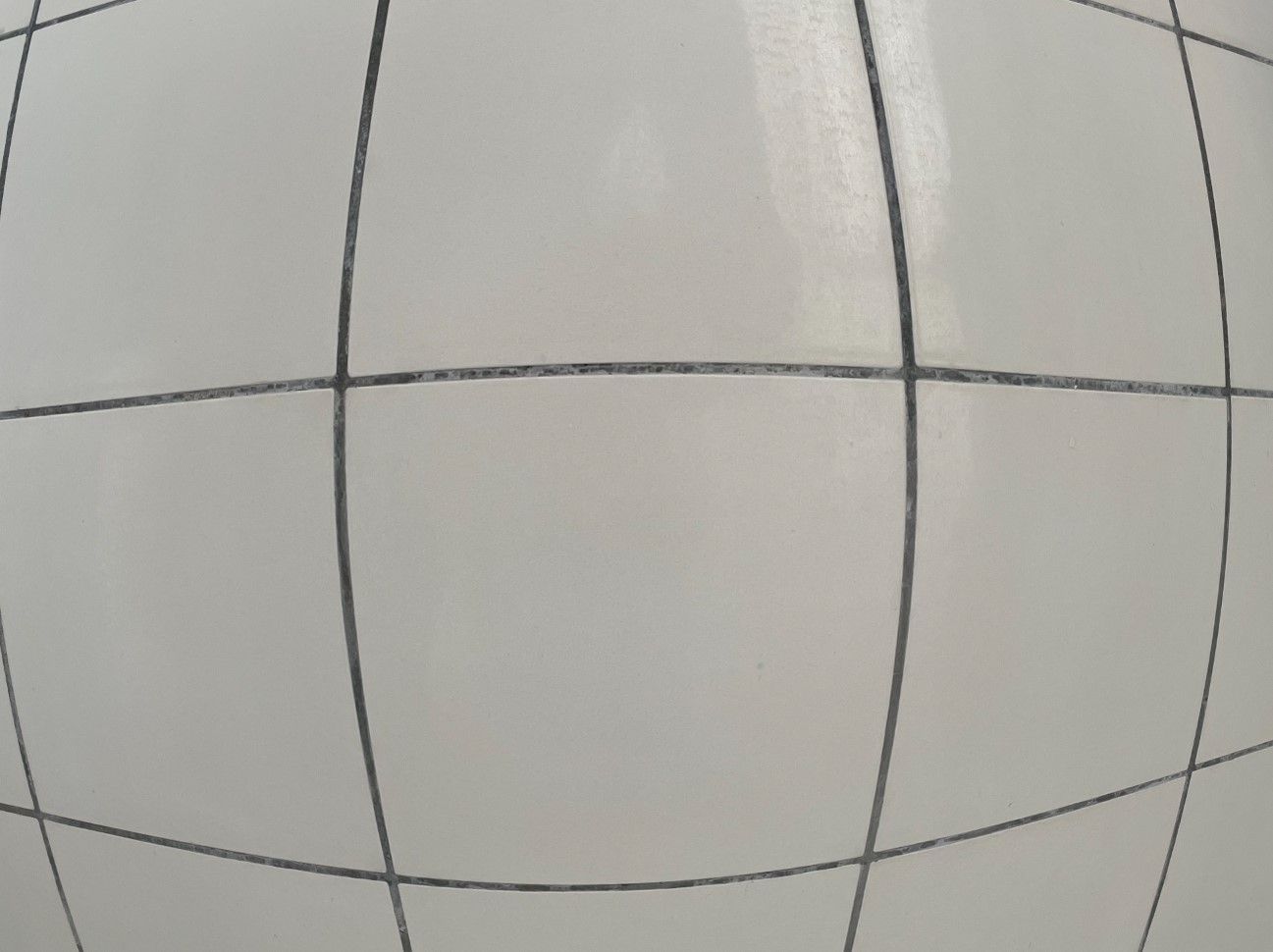

In my reviews I don’t test distortion or vignetting. The simple reason being that you can fix this in Lightroom with a push of a button. Only for demanding architecture or real estate photographers can I imagine that distortion and vignetting would be a problem, and I am pretty sure they are not in the market for a 85mm.

Conclusion

Pro:

- Super sharpness, both center and corners

- Super contrast, both center and corners

- Light – 350 grams

- Ok build quality, albeit no gold ring from Nikon

- Well working manual focus ring

- Takes filters with no issues

- Good handling of flare and ghosts

- Price performance

- Works on Nikon entry level cameras

Con:

- Not the widest of wide – there is the 1.4G to mention an alternative

- Some aberrations in high contrast areas wide open

- Not for videographers (flare too well controls + some focus breathing)

- AF not the fastest in the AF-S family

- Not sure how long-term durable the build quality is

You probably have picked this up reading the review above, but I absolutely love this lens. It is clear to me that all attention has been given to the internals of this lens, and hence you get a “budget-feel” lens on the outside and a top performer on the inside. If you are to prioritize, then if you ask me, this is as it should be.

Right now, I cannot think of a lens where the price / performance ratio is better than this one when we are talking modern lenses (vintage lenses you buy on a flea market may have a better ration, but that stems from the price primarily). So if you need a 85mm prime from Nikon, this one should definitely be on your short list.

My only concern is if the lens will stand the test of time – will it survive the constant use in a demanding pro environment? I am not sure; maybe better to go with a gold ring lens if you are a demanding pro.

Video link

Related reading

Nikon AF-S 16-35mm ED 1:4G lens review

Nikon AF-S 70-200mm F2.8 G VR II lens review

Nikon AF-S 50mm 1.8 G lens review