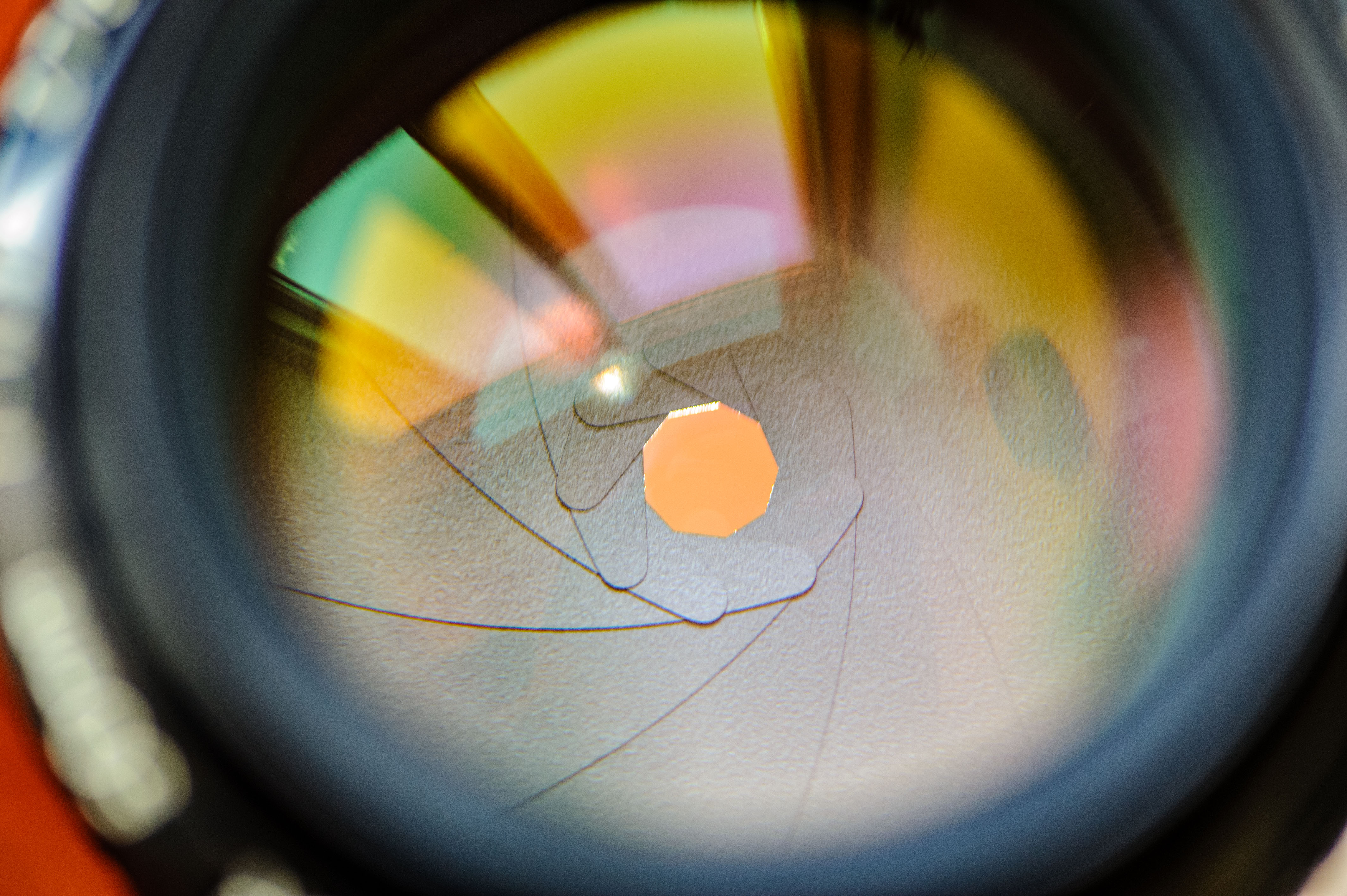

Aperture blades sit inside the lens and are small pieces of fabric that move to reduce the size of the area that lets light pass on to the senor or film in the camera. The aperture blades and their position determines the aperture setting of the lens. In the picture below, you san see how the blades form a small circle:

On many lenses you can actually manually move the aperture ring back and forth and see how the size of the aperture changes. Take the lens off the camera and look into the lens the same way the light travels, as you move the aperture ring from min to max aperture. This is probably one of the best ways to understand how the blades work and what they do.

It may seem silly to not use all of the lens now that you have it available! Why reduce the amount of light that travels through the lens? The answer is can be that you want to control the depth of field that the lens produces: reducing the aperture size increases the depth of field. Or maybe you are outside on a bright day, and simply have to reduce the amount of light that the lens takes in to avoid over exposing the images. The pupil in your eye does exactly the same!

Blades come in 2 versions basically: straight and rounded. In the image above, the lades are straight, as this is a very old lens design – the Nikon 50mm 1.2 AI lens. Straight blades gives great sun stars but may also give bokeh balls that are not round – rather they have small edges. Rounded blades have the opposite effect – great bokeh, but less great sun stars.

When a lens is at is maximum aperture (lowest f/stop number) it is termed to shoot wide open. When a lens is wide open, the aperture blades are not engaged, and the bokeh shape is the same irrespective of straight versus rounded bladed.

When a lens is at its minimum aperture (highest f/stop number) it is closed down. Some lenses can close down to such a degree that the light almost find is troublesome to travel through the small hole that the blades leave open. When that happens, the image appears a bit out of focus (soft) and this is due to diffraction. So be careful not to close down the lens too much (f/16 and higher f-stops is typically where you see diffraction to set in).

The number of blades also varies. Typically older designs had fewer blades than what we see today. You can find the number of blades in the lens specification. In the image above there are 9 blades, which is quite high for a lens that old.