Write with light

Although Latin will never be my forte, I seem to remember that photography stems from the words “writing” and “light”, i.e. writing or creating with light. So bearing this definition in mind, does low light photography then make any sense? In a word: Technically: no, emotionally: yes.

Signal to noise

Signal to noise. Sounds complicated, right? And it is, if you want to be an engineer and dive into this interesting concept. Lots of math and complexity. But for us photographers, all you need to know is that light is a signal and that your camera is a system that inherently holds or produces noise. So there is a balance between the input in the shape of light and noise during the production of the output, the image. That balance is signal to noise. And the stronger the signal is relative to the noise, the better, i.e. the more clean the image will appear.

When shooting in low light, the signal to noise ratio is appalling! Your camera struggles to “see” if there is light or darkness, and it makes mistakes! And the mistakes show up in the shape of grain and noise and washed out colors. The camera sensor simply gets so little light, that the noise is as strong as the light, and hence the sensor starts mistaking noise for light. And that is not good.

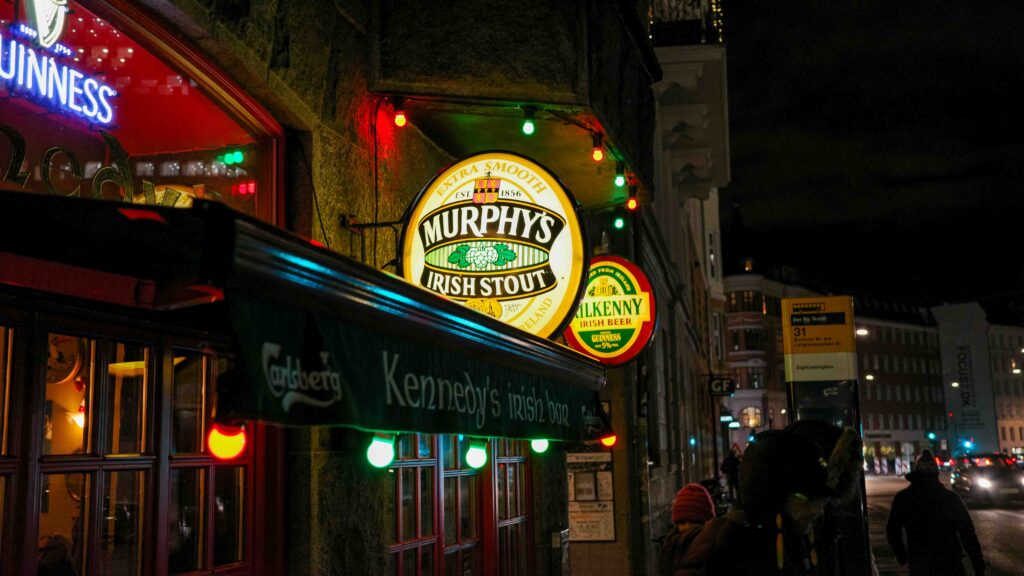

So the obvious solution here is to add light – a big fat flash that will lighten up half the city and take out the noise, right? Well, right from a technical perspective. But people sitting in a dimly lit restaurant may find that this is exactly what will break the cosy atmosphere and you will not capture the emotion of the scene, as the added light ruins it all.

So the way forward is to find a way to capture the scene with very little light, and as with so many other aspects of photography there is no silver bullet. You have to find the optimal compromise.

What to do

First of all you need to make sure you get as much of the ambient light in the scene into your camera, so the faster your lens is (larger aperture) and the larger the camera sensor is, the better. Just like a big bucket gathers more water when set out on a rainy day than a small bucket, your camera will gather more light the larger the surface to gather it. And here the “size” of the (fast) lens and the size of the sensor is a remedy. But it comes literally with a price, and full frame glass is a lot heavier than say APS-C glass.

Your next friend when there is little light available is time. The longer you can let the shutter stay open, the more light will be gathered obviously. But with time comes two new enemies: camera shake and motion blur. You can use both camera shake / movement and motion blur for artistic purposes, but if not, movement while the shutter is open is not your friend.

Camera shake can be countered with a tripod or maybe just leaning the camera towards something stable. When I am in town at night, I often use lampposts or other stable objects to give some level of stability to the camera. Next, you can invest in a camera (or lens or both) that has image stabilisation. This helps a lot and has made it possible for me to shoot sharp handheld images with shutters open at 1/4th of a second – something that would be completely impossible without stabilisation.

Motion blur is when your subject moves while the shutter is open. It can be hard to avoid when you are shooting fast moving objects at night e.g cars on a highway. One technique is to follow the subject with the lens (panning), so the subject is kept in the same position in the frame and everything else gets blurred. This requires some training, but is great fun when you succeed! If you just want to take pictures of people in a restaurant, keep an eye out for an arm moving or a glass being lifted – maybe that is not the right time to hit the shutter!

Cranking up the ISO is what many do! If not deliberately, then because the camera is in some automated mode where it struggles to find a way out! Shooting at high ISO is often necessary in a low light scene, but be aware that in digital photography the sensor has the sensitivity that it had when it left the factory! When you turn up the ISO value, it is factor applied to the readings of the sensor. You can see this as camera internal post processing being applied. So both signal and noise will be amplified. It is just like an old tired analogue radio with a muffled sound and bad reception of the signal: turning up the volume will not make it sound better, as both music and noise is amplified. So try to limit or cap the use of ISO – I normally do not go beyond ISO 3200, but a “max acceptable level” varies from camera to camera.

Finally, it is not only the exposure that struggles in low light, also your focus system will struggle. You may find that your otherwise super stable and fast (daytime) auto-focus system starts hunting and acting weird. And images out of focus may result. The remedy here is manual focus. Yes, I know, if you rely on auto-focus in your daily work, switching to manual focus is not what you hoped for. But it may be the very thing standing between you and some great low light images. So use all the focus aid systems available in your camera: zooming in in the viewfinder or focus peaking highlights or focus confirmation dots. Take all the help you can get as you take control of the focus.

Next step

I know that photography can be a pain: you were hoping for a quick fix only to learn that photography as per usual is about finding the best compromise. But don’t give up: low light images can be very rewarding and capture a tranquil scene or sentiment that no other type of photography offers. So I hope you will take up the low light challenge – the rewards on the other side is worth it.

Related reading

Flash photography – why bother?

Thank you for your clear article about low-light photography. I am enjoying your daily treats!

If you will allow me to be “fussy”. In your recent article, you correctly state “… that light is a signal and that your camera is a system that inherently holds or produces noise …”. However, in addition, the incoming light also “holds” noise.

By analogy, imagine a grid of buckets on the ground during a rain shower. The buckets are analogous to the sensor pixels, and the raindrops are the light arriving. Imagine the rain was a “light shower”, with just one raindrop per bucket on average. This is equivalent to low-level but uniform light over a camera sensor – a low-light image of a featureless object. Some buckets will receive 0, 1, 2, 3 or maybe even 4 raindrops in them, even though the average is exactly one raindrop per bucket. It is the same for light on a camera sensor. That spread in raindrop/light collection is also noise, and there is nothing we can do about it. Technology can eliminate much of the additional camera and detector noise. For example, the buckets in my analogy add zero noise, as each raindrop is accurately counted!

If, however, there were 1000 raindrops per bucket, then some buckets might collect 980 and others might collect 1020. There is still variation – noise – but compared to the average, 1000, the fluctuations between buckets are much less noticeable.

So, I would alter your sentence to: “… that light is an inherently noisy signal and that your camera is a system that can produce additional noise …”

Thank you Mike! I think you have a point. I also sense that you are not new to photography?