Photographers often question their current gear and is constantly scanning the market for better options with more advanced features. There is often no need for that. Your good old trusty DSLR will do just fine!

Gear acquisition syndrome (GAS) is a common disease amongst photographers.

Yes, a more modern camera may have more megapixels and face recognition and the like, but I would suggest that you put these considerations to a side and focus on getting to know your camera. Not that you need to know and understand each and every detail about the deepest menu system, but more the basics related to focus and exposure. Here I will take you through some of the important aspects of your camera and gear.

Megapixels

How many megapixels do you need as a portrait photographer? Not many. I have shot with my trusty old Nikon D700, and it is a 12megapixel camera, and used the files to print in size 70 x 100 cm and the client was happy as can be. The thing is, the larger you print, the larger the viewing distance.

If you see a large print on a wall, your natural reaction is to take a step back to allow you to take it all in. Otherwise you will be viewing the image as you would a tennis match – your eyes would go back and forth, and most don’t do that, but take a step back. If you pass a billboard, try to go up close. You will see that the resolution is very low (= looks horrible!), as it is intended to be viewed from far away.

The most common reason for wanting a lot of megapixels is to be able to crop, but if you frame your images carefully, then cropping should not be necessary. When the first digital cameras came out, they had only about 8 megapixels, but it was still amazing images the pros could produce. So don’t worry about the number of megapixels. Worry about filling the frame with your subject, and you are good to go.

Sensor size

Another common worry amongst photographers is choosing between APS-C and full frame. There are differences, granted, and you need less light with a full frame camera. But modern sensors (i.e. produced within the last 15 years) are so good that I find the difference to be negligible. You can shoot amazing images also with APS-C. So I would not worry about the sensor size.

File format

Your camera most likely offers different file formats – the one with most information is RAW and that is the format I recommend. You will get the most flexibility and headroom if you shoot raw. But there is a downside of course, and that is the space it requires both on your memory card and your computer.

You can do fine with say a JPG file, but you cannot recover so many details from the shadows or highlights if you need to, when your exposure is a bit off or the dynamic range of the scene stresses the dynamic range of the camera. So it is a balance between the need for post processing flexibility and saving disc space. Your call. My suggestion is to go for the flexibility and then have sufficient storage to accommodate the raw format.

Exposure parameters

Exposure is obviously important. But with digital photography and raw file formats, I would say less so now than in the film days. You can do a lot of adjustments to exposure in post when you shoot raw, and also you can preview the images on the camera’s rear LCD, along with a histogram. So if your exposure is off, then the options for learning about this while shooting are many.

But, there are 3 vital parameters you need to work with when we are talking exposure: ISO, aperture and shutter speed.

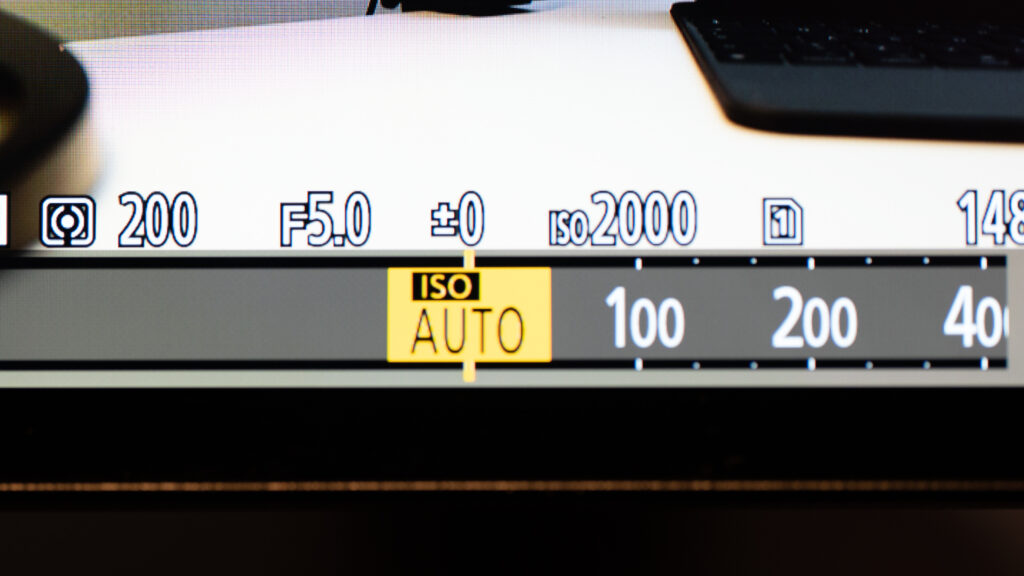

Your camera comes with a base ISO value, typically 100 or 200. From here you can turn up the volume and the higher ISO, the less light the camera needs to expose correct, all things being equal. The down side is that you will pay a price in terms of grainy images and washed out colours if you go too high on the ISO.

You can test this with your specific camera model, but I would stay below or at ISO 2000 as the limit. Different cameras have different limits to when the images start to turn bad, so give it a try with your camera model and see where the pain point starts to set in and stay well below that.

Auto ISO can be a great help. It means that the camera sets the ISO automatically to give the correct exposure. Typically you can limit the ISO so the camera will not go over a certain value – I recommend that you set this limit so you are sure not to come home with grainy images. And then I recommend that you switch Auto ISO on – it gives a bit more headroom for the shutter speed and aperture.

Shutter speed

Speaking of shutter speed, the reciprocal rule says that you should not go slower than the reciprocal value of your focal length. So if you are shooting at 85mm, then 1/85th of a second is the slowest you can go. Modern cameras with vibration reduction in both lens and camera have moved these limits and allow much slower shutter speeds, but if you have a good old DSLR with no vibration reduction, then the reciprocal rule is a good guide.

Aperture

If you ask me, aperture is the most important parameter in the exposure settings, as it dictates the depth of field. The more closed down the aperture is (higher f-stop numbers) the more depth of field (DOF) you get. And depth of field can be a life saver if you don’t manage to get the focus just right – the DOF introduces a “forgiveness” factor that can save you from minor misses on focus.

Google a depth of field calculator app and load it into your smartphone. Put in the parameter from your camera and the settings you plan to use and see what DOF you get. I prefer to have a DOF of at least 30-40 cm, so that when I focus on the eyer, the person in focus is sharp front to back. Notice that even though the aperture has a big influence on the DOF, the distance to the subject has even more. So getting some space between you and the subject can be absolutely vital for getting the DOF you want.

Exposure modes

Your camera will have several exposure modes: PASM, meaning program, aperture priority, shutter priority and manual. To allow you to focus on the client and the shoot, I would stay clear of manual mode unless you are very comfortable with keeping an eye on the light meter. Aperture priority means that you are the boss when it comes to the aperture, and the camera selects the shutter speed. For shutter priority it is the other way around. Program mode means that the camera sets both the aperture and the shutter speed – this is the mode where you have less control.

Finally, many cameras also have a Auto mode. It is the same as program mode, but in addition the camera has pre-selected and locked a number of other values so it is in “point and shoot” mode.

I typically shoot in aperture priority to control the DOF, and the camera then selects the shutter speed. And in addition I switch on auto ISO, so the camera has to variables to play with to get the exposure right. But I always try to keep an eye on the shutter speed, to make sure it does not get too slow.

Compensation

Your camera probably has an exposure compensation button. It typically sits close to the shutter release button and has a +/- sign. If you push that button, your can use the front or rear command dials to set the exposure compensation in stops of light.

It can be very useful if you don’t agree to the cameras automated metering, i.e. you find that it systematically exposes to much or too little, or you just want to protect the highlights. The adjustment of the automated exposure can be really useful, but be careful when you have it activated – you may forget it is on! Keep an eye out for the metering scale – it will show if you have compensation turned on.

Metering modes

Your camera probably offers a number of metering modes. The most automated and advanced is named matrix or weighted metering. That is the one I would recommend you to use.

For portrait there is an alternative to consider and that is the center weighted mode. It will prioritize metering according to the amount of light in the center of the frame. This can be useful if you are shooting against a very bright background like at white backdrop.

No matter which mode you choose, it will not change the amount of ambient light- only the way the camera interprets the light.

Shake

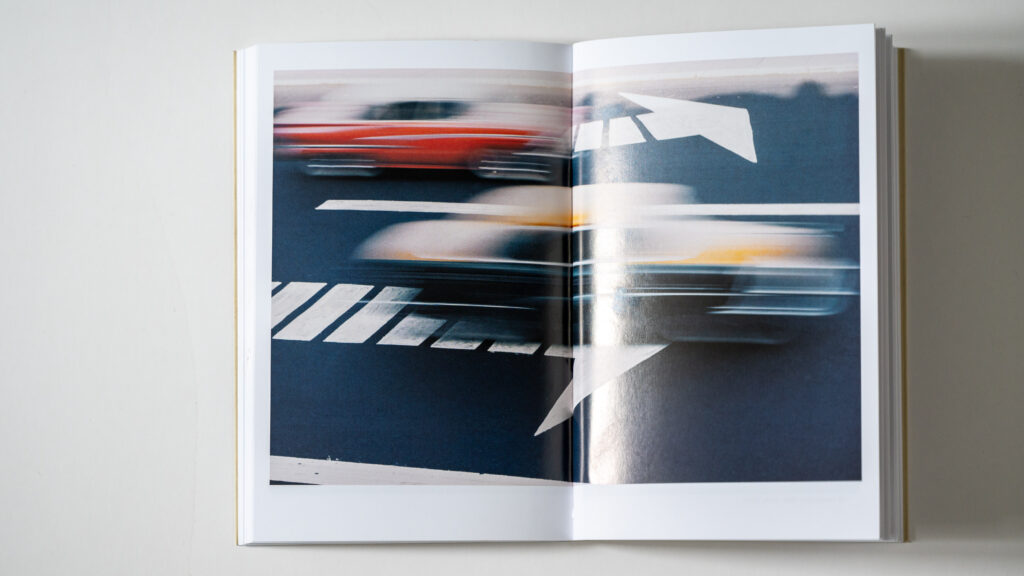

You don’t want shake or movement. Camera shake is when the camera is moved while the shutter is pen. Movement is when the subject moves while the shutter is open. The slower the shutter speed, the bigger the risk of shake and movement there is.

Shake and movement is not what you want in portrait photography. You can use it creatively for some images, but my guess is that for the most part your client would like to have images that are not blurred. And shake and movement will look blurred. Many mistake images with blur for being out of focus, but the cause is different.

A tripod is a good way to mitigate camera shake. But it does take up space in your backpack, and although modern tripods comes in carbon versions, there is still a weight penalty to be paid. If you are to do 100 corporate headshots, then you definitely want the camera to be on a tripod to make sure you get exactly the same angle and position for each image (along with a cross on the floor to indicate where the employee is to stand).

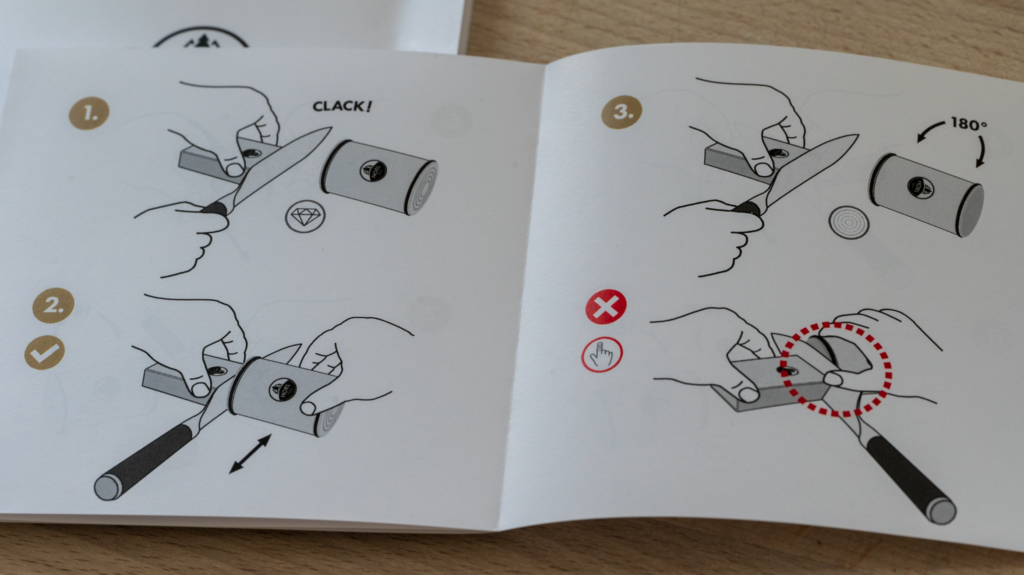

When we are on the subject of tripods: consider to get an l-bracket. It makes shooting in portrait mode so much easier without tipping the balance of your camera on the tripod.

White balance

Your camera probably has a button named “WB” or a quick menu where you can set the white balance. The white balance is something camera producers generally try to make accessible easily.

Don’t mix light sources with different colour temperatures – it is a safe route to trouble, unless you shoot black and white!

You will probably find that your camera offers a lot of options for white balance settings. Don’t worry and put the camera in automatic mode. Modern cameras have an excellent white balance automatic system, and you can always tweak the white balance in post if you are not happy with the chosen Kelvin value!

However, be careful not to mix two colour temperatures! I once photographed a birthday where the party was held inside (candescent light) but there were some very big windows also that contributed with a lot of natural light (sun). When I shot people standing close to the window or even worse: with the window as a backdrop, I got two different colour temperatures mixed! The result: Either their skin tone looked absolutely horrible and the room colours looked ok, or their skin tone looked natural and the room had the most weird colours! That taught me to not mix colour temperatures!

Focus settings

Your camera probably has a lot of options for setting focus, and with mirrorless cameras it has gotten a bit more complicated adding face recognition and even recognition of animal faces! So many choices!

My advice is: shoot with a focus option where you control what the camera selects to focus on. In auto focus mode, you have no control of what the camera focuses on, and it will typically select whatever is the closest to the camera. But that my not be what you want it to focus on.

I prefer a low tech option that gives me control. So I usually shoot with a small focus point that I can move around with the command wheel on the rear of my camera. If you don’t have time to move the focus point around, then move the camera so the focus point is on the eye of your subject, half press the shutter to lock focus, recompose (i.e. move the camera so you get the framing you want) and then press the shutter fully to take the picture. When you’ve done this a few times, it quickly becomes second nature.